You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know

“True wisdom comes to each of us when we realize how little we understand about life, ourselves, and the world around us.” — Socrates

Welcome!

This is the second, and key, essay in the foundation series on human behavior. In the first foundation essay, Why “Seeing The Mountain”?, we covered the many ways a metaphorical mountain can be viewed and understood. In this essay we introduce:

The enormous amount of information that is available to us

How imperfectly we take in that information

How we store that information

How well we remember that information

How well we recount that information when needed

Much of human behavior that mystifies us is rooted in our imperfect recollection of incomplete information, and how we make (often subconscious) decisions as a result.

What we cover today will be the basis for upcoming essays on human behavior that will empower you and improve your understanding of those in your life.

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.“

~ William Shakespeare ~

Infinite information and the finite brain

The Earth’s surface is about 196.9 million square miles (510.1 million kilometers) while the typical person will only travel 30,000-50,000 miles (50,000-80,000 kilometers) in their lifetime; much of that over the same paths. Most people have not visited more than 10 of the 200 countries on the planet with almost 1 in 5 having never left their own country. Over a lifetime the typical person will have personally met less than 0.01% of the world’s population (estimates and individual experiences vary widely).

That’s our experience on this planet. The Earth is ~7,918 miles (12,742 kilometers) in diameter. It’s one of 8 planets revolving around our star (the sun). There are 100,000,000,000 to 400,000,000,000 stars in our galaxy and possibly over 100,000,000,000 galaxies in the observable universe. It’s unknown how large the actual universe may be.

As for the accumulated knowledge on the planet, there have been over 134,000,000 books published. In one minute, over 500 hours of videos uploaded to YouTube, over 66,000 pictures uploaded to Instagram, 1,700,000 posts to Facebook, 16,000,000 texts sent, and 231,400,000 emails sent (2022).

Your knowledge and experience, which have taken you this far, are an insignificant sliver of all that can be known. That’s also true for the other 8,000,000,000 people on the planet. The most educated and experienced person in the world is still left with an insignificant sliver of knowledge. Yet, that sliver of knowledge we each possess is valuable and, working together, humanity is making enormous progress.

The amazing brain

Our brain weights about 3 pounds (1.4 kg). In that brain there are about 86 billion neurons and about that many glial cells, which support the neurons. The brain collects its information from seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touch, body position, temperature, and pain (there are more senses under certain definitions). Here are some of the biological limitations for the first four senses listed…

Seeing the world

Our eyes can see photon wavelengths from 380 nanometers to 720 nanometers. Wavelengths range from a few trillionths of a meter to several kilometers, so what we see is just a tiny fraction of the information available.

The typical person can perceive about 1 million unique colors. A few gifted individuals, tetrachromats, have a genetic mutation that allows them to see 100 million colors while a few less gifted individuals can only see 10,000 different colors.

But humans don’t have the best eyesight on the planet.

A gecko can see color 350 times better at night than a human. An owl can see objects in 1/100th the light than a human. A wedge-tailed eagle can spot a rabbit from thousands of feet away. The bald eagle’s vision is 7-8 times sharper than a human’s. Genetically, we are only able to perceive a fraction of the visual information around us.

Hearing the world

The typical human ear can hear vibrations from 20 hertz to 20,000 hertz and that range shrinks as we age. A dog can hear up to 45,000 hertz and a cat can hear up to 64,000 hertz. Wolves can hear sounds up to 10 miles (16 kilometers) away. Sadly, the hearing capability we do have, declines as we age. Even those born with perfect pitch see their capabilities maddeningly change as they enter middle age.

Smelling the world

Humans have a very strong sense of smell. We can detect up to 1 trillion distinct smells. While humans are capable of distinguishing many scents, many animals are able to detect weaker scents. African Giant Pouched Rats are used to smell for landmines and to detect tuberculosis in lab samples. The Great White Shark can smell 1 drop of blood in 10,000,000,000 drops of water. A bloodhound can trail a scent that’s 13 days old and can follow a scent up to 130 miles. An African Elephant, the animal with the strongest sense of smell, can smell water up to 12 miles (19.2 kilometers) away.

Tasting the world

Compared to the other senses, it’s much harder to compare a human’s sense of taste versus that of various animals. Evolutionarily, taste developed to identify potentially dangerous food we shouldn’t eat and to identify foods with needed nutrients.

By the numbers, humans have between 2000-8000 taste buds; each with 50-150 taste receptor cells. Catfish have around 100,000 taste receptors on their body. Cows have up to 35,000 taste buds and octopus have around 200 suckers, each with 10,000 taste receptors.

However the sense of taste is intertwined with the sense of smell. Our sense of smell accounts for 80% of what we taste. Our brains combine the chemical information from what our noses detect with the chemical information from our tongues related to salty, sweet, bitter, sour, and umami (some sources identify more taste types). The information from the two senses are then coalesced into a ‘flavor’ of what we’re eating.

Larry Lanouette temporarily lost his sense of smell due to the effects of chemotherapy. Anosmia significantly altered his sense of taste and his ability to enjoy eating. He tried to draw on his memory to make eating more pleasant.

“When I’d eat food, I remembered what it was supposed to taste like, but it was a total illusion,” he said. “Eating became something I had to do because I needed to, not because it was an enjoyable experience.”

It should be no surprise that, like our other senses, our ability to taste also changes as we age.

In recent years, researchers are finding that humans (and other animals) have sensors in their guts that notify the brain that amino acids and fatty acids have been consumed and to seek out more of what contained those nutrients. It’s a taste that’s at the below conscious level.

Absorbing the information

Now that we’ve covered what information is available and what we can detect of it, we’ll delve into what the brain is able to retain and remember.

The brain has a limited capability of taking in information and analyzing it. In this video, there are eight basketball players passing the ball around. Can you accurately count how many passes were made by the players wearing white? On my first try, I missed one though I thought I was carefully counting. Can you count them all?

Our brains are incapable of processing everything we sense; even when we focus intently on a short video. Our brains consume a lot of energy. They account for only 2% of our mass but consume 20% of our energy (calories). The body’s ability to fuel the brain remains constant so the brain adjusts to higher processing needs by ignoring information it deems irrelevant. As you watched the video, the brain ignored everything but the players in white.

'Our findings suggest that the brain does indeed allocate less energy to the neurons that respond to information outside the focus of our attention when our task becomes harder.

'This explains why we experience inattentional blindness and deafness even to critical information that we really want to be aware of.'

If you’re threatened, your vision narrows and your hearing drops away. When you’re anxious or panicked, which requires a lot of energy, the brain becomes less able to think clearly. In some extreme moments, conscious thought can nearly cease and the limbic system is left to “run the show”. This is sometimes referred to as a mental freeze (which can sometimes protect you from the full effects of trauma).

“The sin of inadvertence, not being alert, not quite awake, is the sin of missing the moment of life-live with unremitting alertness.”

Joseph Campbell

Memory processing

In addition to being limited to the amount of information we can take in, we have a limited ability to retain that information in our memory. Without resorting to memory tricks that bring assistance from other parts of our brain, we can briefly retain about 7 pieces of information in working memory — such as a phone number or a list of ingredients. And that can fade away in as quick as 20 seconds. This function is similar to how a computer uses RAM to process information before being transferred to a storage device/drive or discarded.

During the course of the day your brain accumulates bits and bobs of information in the hippocampus and when we sleep it gets transferred to more permanent storage. Good sleep can improve the retention of facts 20-40%.

WARNING: This section on memory processing is only a bare introduction into the basic concept of how memory works. Academic research into memory has differing models on how memory is believed to work and these models use differing terminology. If this area interests you, I suggest researching the topic on your own for a more thorough and balanced take on the field.

“The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.”

~ Bertrand Russell ~

Memory retention

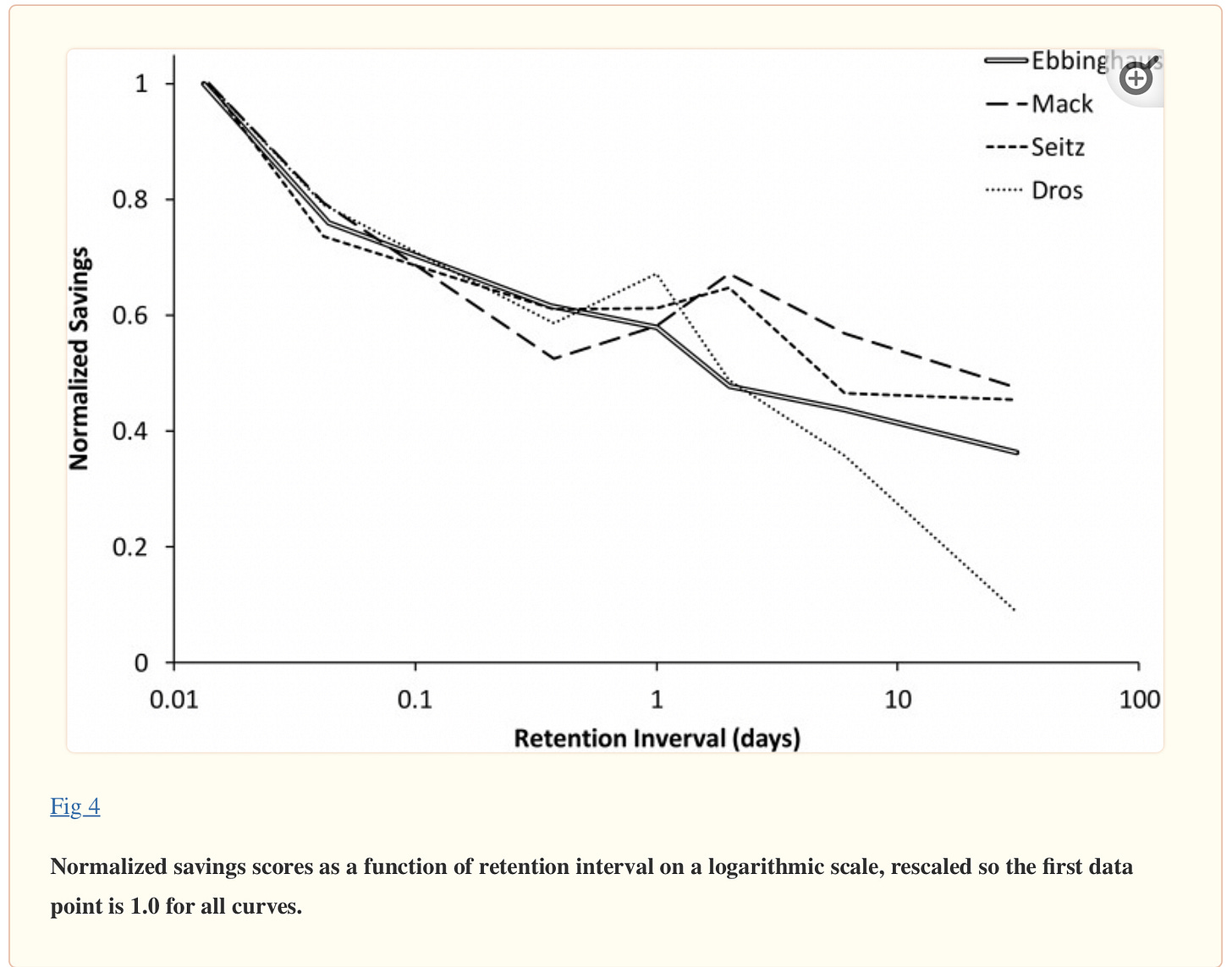

Our memory is a sieve. Synapses rewire and die as well as brain cells dying and new cells being created. Memories fade faster than most people realize. Roughly 30% is lost in the first two hours after learning and over 40% is lost in one day.

Research on memory continues to unfold, but what we do know is that memory is fallible, and shockingly so. Most of our most cherished memories are confabulations, an intricate blend of fragments from our past, images from dreams, movies, books, and even other people’s memories assimilated as our own. This is the fantastic, frustrating, perplexing nature of memory: It is endlessly redefining and refining what we remember. Ask three siblings about a shared experience and you are likely to get three different versions of the event.

To compensate for missing and lost information, the brain inserts created information in the gaps. It uses your experience to insert pieces that make sense to the memory. It might insert a snippet from another memory or it will insert a piece of what somebody else said happen.

In one study on the audience-tuning effect, participants watched a video of a bar fight. In the video, two intoxicated men get into a physical confrontation after one man has argued with his friend, and the other has seen his favourite football team lose a match. Afterwards, participants were asked to tell a stranger what they had seen.

The study’s participants were split into two groups. One group was told that the stranger disliked one of the two fighters in the video. The other group was told that the stranger liked this same fighter. Unsurprisingly, this extra information shaped how people described the video to the stranger. Participants gave more negative accounts of the behaviour of the fighter if they believed the stranger disliked him.

More importantly though, the way people told their story later affected the way they remembered the fighter’s behaviour. When participants later tried to remember the fight in a neutral, unbiased way, the two groups still gave somewhat differing accounts of what had happened, mirroring the attitude of their original audience. To an extent, these participants’ stories had become their memories.

Our memories are not like a recording, but more like pieces of a puzzle that are cobbled together.

Many people believe that human memory works like a video recorder: the mind records events and then, on cue, plays back an exact replica of them. On the contrary, psychologists have found that memories are reconstructed rather than played back each time we recall them. The act of remembering, says eminent memory researcher and psychologist Elizabeth F. Loftus of the University of California, Irvine, is “more akin to putting puzzle pieces together than retrieving a video recording.”

Another memory phenomena is “blocking”. You may retain a memory, or a reasonable facsimile of one, yet not be able to immediately retrieve that memory. You’ve experienced this when you couldn’t immediately remember a song title, singer, or actor when telling a story but later remembered it on the drive home.

“Memories are not fixed or frozen but are transformed, disassembled, reassembled, and recategorized with every act of recollection.”

~ Oliver Sacks ~

Putting this all together

To summarize, we are exposed to an infinitesimally small percentage of the available information in the universe. Of the information we are exposed to, we are only able to absorb a sliver of that information. Of the information we absorb, we retain only a small percentage of that, and we fill in the blanks with manufactured information. Then much of that is lost over time. With what remains we need the experience and tools to make the best use of it. As we are human, we’ll do that imperfectly.

Finale

In the first foundational essay we discussed the many different ways our metaphorical mountain can be viewed. In this essay we discussed the enormity of that mountain and why we are unable to see much of it. The next essay in this foundational series is on how we use groups to fill in the gaps of what we don’t know and the associated challenges. With society becoming increasingly siloed and isolated, group dynamics are becoming increasing impactful on society; making this upcoming essay particularly useful.

Exercises

To be done when you are in a non-distracting environment.

Think of a time when a major problem arose because you thought you had all the needed information, but didn’t.

How has that experience affected your decisions going forward?

Identify a key piece of information you’re missing for a needed decision.

What options do you have to fill in that knowledge gap?

In Closing

Thank you for visiting today. If you found this newsletter interesting, subscribe by clicking the button below. Please like, comment, and share to support this newsletter. If you have any friends or family who might find this content interesting please recommend this newsletter to them.

Your friend,

DJ

Crikey this is fascinating stuff. Thank you.

Hey, What a great article you wrote! This is actually going to be a great complimentary piece of a topic on my to write list (not my personal Substack, but for my consultancy). A CEO or any leader they would never be able to make the absolute correct decision, But only the best they know under the circumstances (not to mention they are under stress most of the time, which, as you said in your article will limit their ability to process information).

A lot of times you only need a few wrong decisions to be made to waste few millions of funding. So the question is, is there anyway for us to resolve this problem or should we started to consider using AI as our CEOs?