Filling In The Blanks

How our brains adapt to missing information

Welcome!

“Rather than swallowing our pride and simply asking what we do not know, we choose to fill in the blanks ourselves and later become humbled.”

~ Criss Jami ~

In You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know we covered how little we perceive, how little we know, and how poorly we remember. In Our Tribes and How They Shape Us we covered how we use our tribes to help fill in what we don’t know. The last essay, Wisdom of the Crowd, Madness of the Mob, we went over how we take cues from those around us to fill in our knowledge gaps. Today, we discuss how our brains fill in perception and knowledge gaps to ease decision making.

Information overload

The brain is constantly taking in information and attempting to process it. When the brain trips over a piece of information it can’t quickly process, or deems important, it reduces information processing in other parts of the brain and narrows its focus on the problem at hand. Along with this, anxiety increases and the individual becomes less comfortable. With the brain making 35,000 decisions a day, we wouldn’t be able to function if decisions weren’t made quickly. To do this, the brain develops ‘shortcuts’ to fill in missing information. This allows us to make quick decisions but if we fail to understand the processes involved, our quick decisions can become quick and enduring mistakes.

Olive, the other reindeer

“Always remember that it is impossible to speak in such a way that you cannot be misunderstood: there will always be some who misunderstand you.”

~ Karl Popper ~

Hearing is a very imperfect process. Sound waves interfere with each other as multiple sources of sound compete for our ear’s attention. The brain must then process that information in a useful manner. In our modern world we encounter increasingly noisy environments, which the brain has to process in a useful manner.

Netflix reports that now 40% of viewers have the subtitles turned on. One reason that subtitle use is so high is that movie dialog competes with an increasing amount of simultaneous music and sound effects. This sounds great in a movie theater, but it quickly becomes a sonic soup over small, inexpensive TV speakers.

When someone is talking, especially in a noisy environment, our brain has to process the sound into meaningful words. It does this remarkably well by filling in missing sounds and interpreting missed sounds and words to guess what was said. Most of the time we don’t even realize we are missing consonants and vowels.

We sift through sounds, activate and reject countless alternatives, and select one single meaning out of myriad homonyms, near-matches, and possible parsings—even though speakers may have different accents, pronunciations, intonations, or inflections. And, in the overwhelming majority of instances, we get it right.

Our brains must not only interpret words out of sounds, they must also interpret meaning to those words. To do this, the brain uses cues and context to determine what was meant.

Some examples of how our brain’s adaptations can go wrong:

Mondegreens

Mondegreens are misheard versions of phrases, sayings, lyrics, poetic phrases or slogans. The mishearing of these leads to misinterpretations and gives rise to new, similar-sounding sayings that offer new and often unique meanings.

“Olive, the other reindeer” is one of the most well known mondegreens, eventually taking on a life of its own in literature and the movies. The original phrase is “all of the other reindeer”, but because ‘all of’ and ‘olive’ are nearly indistinguishable to the human ear the brain guesses wrong, creating a mondegreen.

Eggcorns

An eggcorn, as we reported and as Merriam-Webster puts it, is "a word or phrase that sounds like and is mistakenly used in a seemingly logical or plausible way for another word or phrase.

An eggcorn is similar to a mondegreen in that the brain fills in the wrong term, but logistically accurate, for what was said.

Here are [two] examples of common eggcorns:

Alzheimer’s disease/old-timer’s disease: Since this neurological condition mainly affects older individuals, some mistakenly believe it’s pronounced “old-timer’s disease.” Despite the similar pronunciation, it’s important to get this one right for reasons of both linguistic correctness and sensitivity.

Coleslaw/cold slaw: This side dish comes to your table “cold,” so you might think that’s the first syllable you’re hearing in its name. “Coleslaw” is a cold dish, but that’s incidental to its actual name. …

Oronyms

The English language is a language of many words with similar or identical spellings and pronunciations but different meanings. Oronyms are paronymic words or phrases with similar pronunciations but different spellings and meanings.

An oronym became the basis for a lawsuit in 2001. A waitress won a monthlong contest to see who would sell the most beer. When she was led out to the parking lot to receive her prize, instead of seeing a new “Toyota”, she was given a “toy Yoda”. The case was settled and her lawyer said she would be able to pick up a new car at a Toyota dealership.

Her brain perceived the sounds correctly, but her unscrupulous manager knew she’d interpret the phrase to mean a new car, not a new toy — as did the rest of the staff.

McGurk effect

In real life, too, we do not have direct acquaintance with the world, but rather we depend on our senses to paint an accurate picture of the world. And how well do they do? Not very well. Our traitorous senses will lie to us on a near-daily basis. …

The McGurk effect is produced when you have a video of a speaker mouthing one phoneme and then you dub over a different phoneme altogether. In this case, the speaker makes the lip movements of “gah, gah, gah,” but the sound “bah, bah, bah” is the substituted in. Oddly, what happens is that you will hear the phoneme “dah, dah, dah.” This is the peculiar result of a dissonance in your perceptions. Your eyes are expecting a certain noise, but your ears provide another. So, with a cartoonish whirring of gears, the brain implodes and produces a third sound — even though it was never actually included in the audio track.

In the last example, the staff of the Hooters restaurant used the context of the contest and (reasonably) assumed that the manager’s vocalization meant “Toyota”. Our brains also use visual information to determine the context of a phrase. Here, the brain perceived a mismatch between what was heard and what it saw, so it created a new auditory perception to “fix” the perceived error. It filled in the blank incorrectly.

Who are you going to believe, me or your lying eyes?

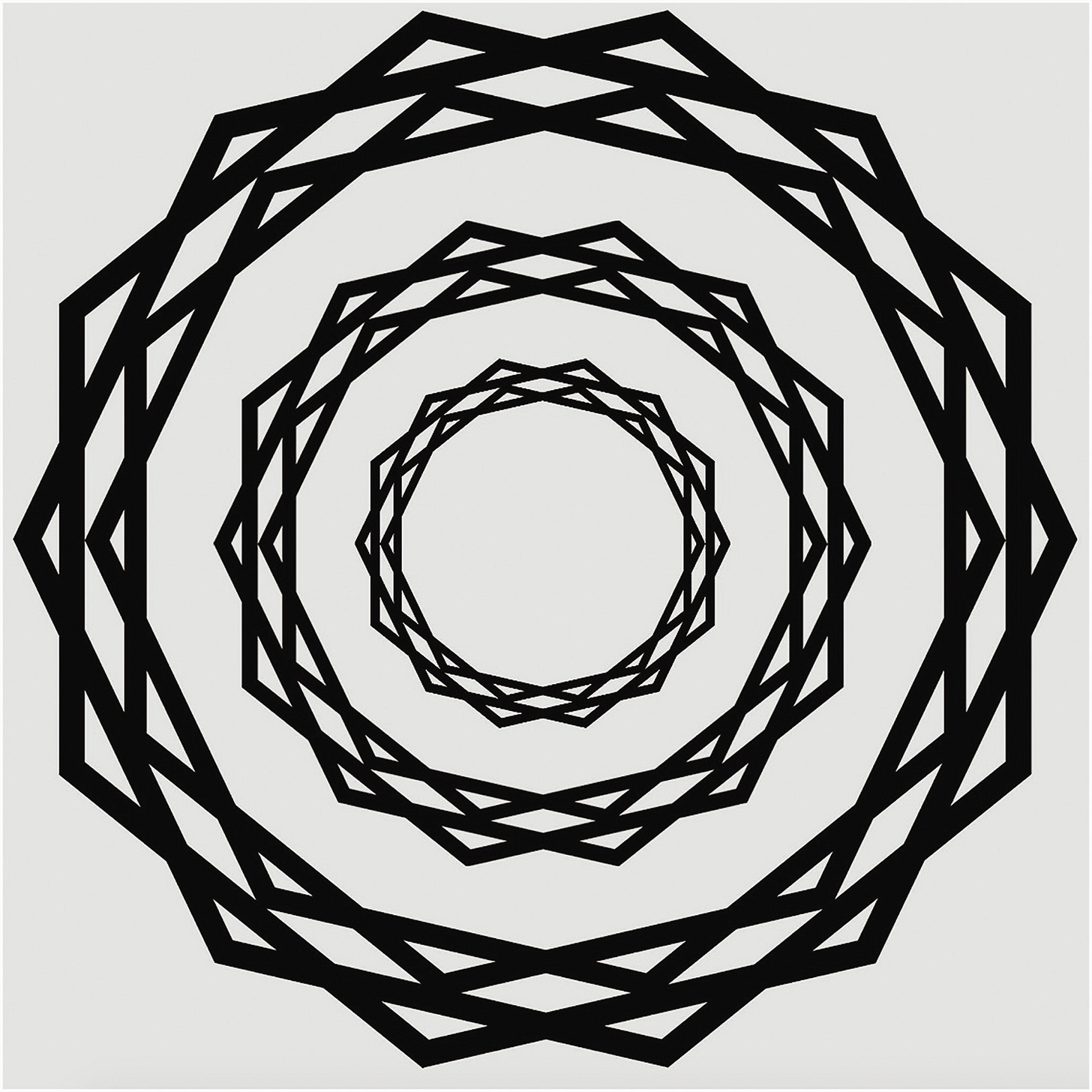

In the picture above, do you see the rays of light emanating from the center? Those aren’t there. Your brain processed the image from your eyes by adding the rays coming out from the center. It’s an illusion and another example of how our brain fills in data in addition to what our senses detect.

This is an example of several visual illusions you can find online. There are approximately 30 different areas of the brain that process visual information. The resulting collaboration can result in visual perceptions, such as these beams of light, that don’t exist (zoom into the image to verify). Most of the time, our visual processing does such a good job that we don’t notice it.

“It’s really important to understand we’re not seeing reality,” says neuroscientist Patrick Cavanagh, a research professor at Dartmouth College and a senior fellow at Glendon College in Canada. “We’re seeing a story that’s being created for us.”

Most of the time, the story our brains generate matches the real, physical world — but not always. Our brains also unconsciously bend our perception of reality to meet our desires or expectations. And they fill in gaps using our past experiences.

We can see into the future… sort of

When light hits your retina, about one-tenth of a second goes by before the brain translates the signal into a visual perception of the world. …

Changizi now says it's our visual system that has evolved to compensate for neural delays, generating images of what will occur one-tenth of a second into the future. That foresight keeps our view of the world in the present. It gives you enough heads up to catch a fly ball (instead of getting socked in the face) and maneuver smoothly through a crowd.

The brain requires a 1/10th delay to process an image, so it fills in this gap with an artificial image. Many illusions, and the livelihood of magicians, depend on this phenomena.

Blind to what we see

As our brain can’t process all the information the eyes take in, the brain ignores information it deems unimportant. If what is being ignored then changes, the brain is unlikely to notice that change. This is called change blindness.

When you’ve failed to see something that is right in front of you (“If it was a snake it would have bit you!”) then you’ve experienced this phenomena. Yep, your visual system is not only creating images that aren’t there, it is also blocking images that are there. It creates a blank that your mind paints in with a previous image.

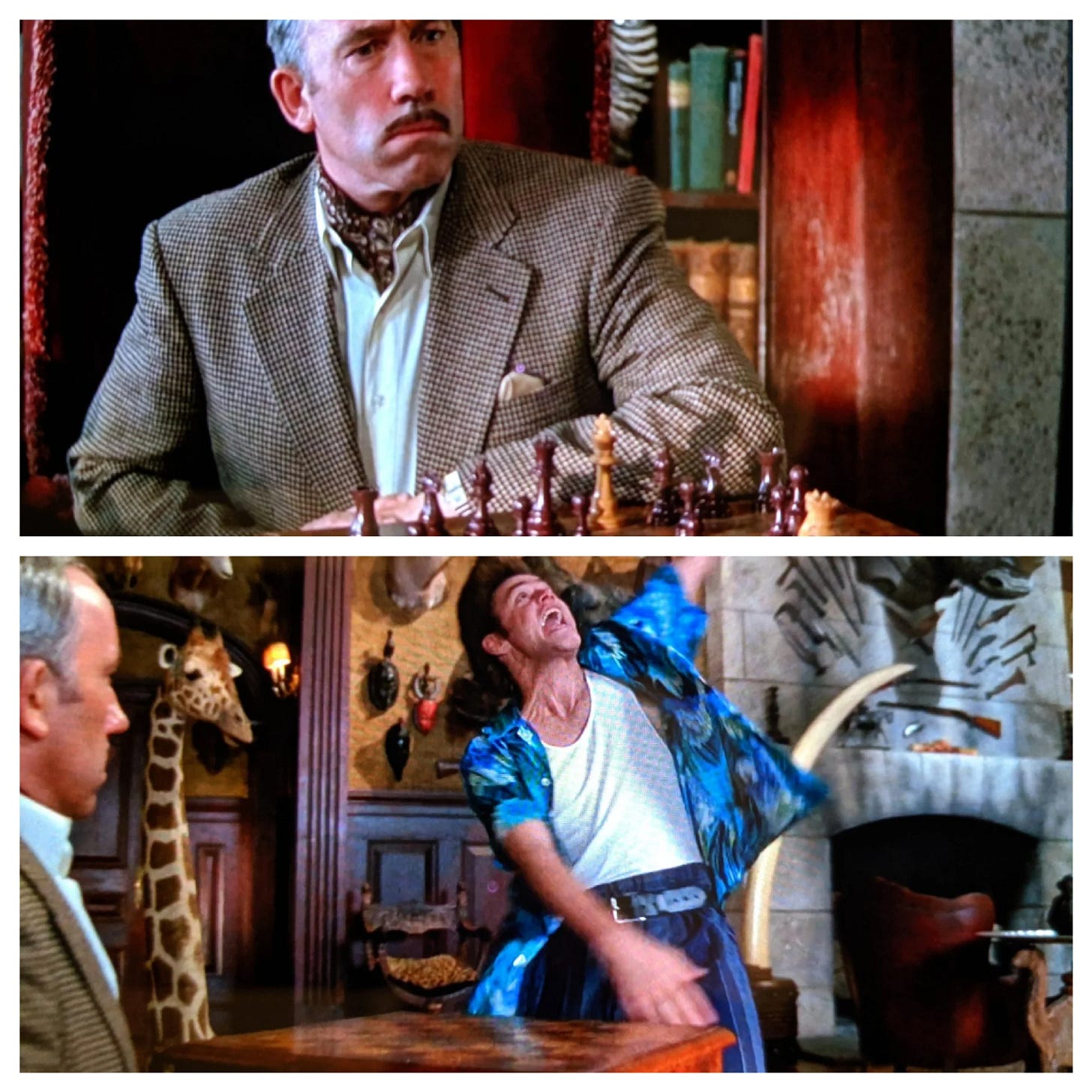

Take the scene in Ace Ventura. We can take in the scene with the chess board, Jim Carrey, and Vincent Cadby. Several shots include the chess board filled with pieces. …

A lot goes on as the camera cuts back and forth, but we’re in the same room. When we get to the scene without the chess pieces, our minds have already started to “fill in the blanks.” We don’t have to visually process every piece of the set the cameras are showing - that would be exhausting. We expect there to be chess pieces on the board. Why wouldn’t there be?

Brain Adaptations

The above are some examples how the visual processing and auditory processing functions of the brain adapt to receiving imperfect information by adding information. Here are some other ways the brain copes with missing information:

Pattern matching

“Humans are pattern-seeking story-telling animals, and we are quite adept at telling stories about patterns, whether they exist or not.”

~ Michael Shermer ~

Our brain craves patterns (Bor, 2012). The talent to recognize patterns is something most people don’t know they need or realize that they already have. If we can turn data into a pattern or rule, then according to Daniel Bor, “near-magical results ensue. We no longer need to remember a mountain of data; we need to only recall one simple law” (Bor, 2012).

A special layer of the brain found only in mammals is responsible. It is called the neocortex, the outermost layer of the brain. Because of its numerous folds, it accounts for 80 percent of the weight of the human brain.

The beauty of patterns for the human brain is that it saves time and energy, allowing the brain to quickly process new information based on how it handled similar patterns in the past.

Humans try to detect patterns in their environment all the time, Konovalov said, because it makes learning easier.

For example, if you are given driving directions in an unfamiliar city, you can try to memorize each turn.

But if you see a pattern -- for example, turn left, then right, then left, then right -- it will be easier to remember.

In fact, what distinguished the human brain most from other animals is its unique ability to recognize patterns and apply those pattens to new information and situations.

This article considers superior pattern processing (SPP) as the fundamental basis of most, if not all, unique features of the human brain including intelligence, language, imagination, invention, and the belief in imaginary entities such as ghosts and gods. SPP involves the electrochemical, neuronal network-based, encoding, integration, and transfer to other individuals of perceived or mentally-fabricated patterns.

Photo by Madison Oren

Heuristics/cognitive shortcuts

A heuristic is a convenient mental shortcut that returns a ‘good enough’ result.

A heuristic, or heuristic technique, is any approach to problem solving or self-discovery that employs a practical method that is not guaranteed to be optimal, perfect, or rational, but is nevertheless sufficient for reaching an immediate, short-term goal or approximation.

Some examples of how we simplify decision making:

Beliefs

“Beliefs are choices. First you choose your beliefs. Then your beliefs affect your choices.”

~ Roy T. Bennett ~

A belief is a firmly held opinion. We develop useful-to-us opinions of how the world operates. Beliefs are not facts and, though we believe them to be true, they might not be. We use our beliefs and knowledge to form our values, and to inform our decisions.

Beliefs are our brain’s way of making sense of and navigating our complex world. They are mental representations of the ways our brains expect things in our environment to behave, and how things should be related to each other—the patterns our brain expects the world to conform to. Beliefs are templates for efficient learning and are often essential for survival.

As we covered in You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know, we possess very little of the available knowledge in existence. To fill this blank, we have beliefs that we use as guides.

Belief systems

“It's naivety to think that we can just change someone's lifetime belief system using some casual conversations. It cannot happen!”

~ Assegid Habtewold ~

A belief system is a collection of interoperating beliefs. They extend beyond religious belief systems. Most of our important tribes, including families and cultures, have their own belief system. Politics is centered around the clash of political belief systems such as liberalism, conservatism, socialism, capitalism, anarchism, or libertarianism. There are philosophical belief systems such as utilitarianism, stoicism, or existentialism. Even within scientific circles there are belief systems with their own theories, postulates, and frameworks. Each belief system is a tool to help fill in the blanks of our knowledge and understanding.

Belief systems are structures of norms that are interrelated and that vary mainly in the degree in which they are systemic. What is systemic in the Belief system is the interrelation between several beliefs. What features warrant calling this stored body of concepts a belief system? Belief systems are the stories we tell ourselves to define our personal sense of Reality. Every human being has a belief system that they utilize, and it is through this mechanism that we individually, “make sense” of the world around us.

Values

“It's not hard to make decisions when you know what your values are.”

~ Roy Disney ~

There are two types of values — terminal and instrumental. Terminal values are the desired result such as world peace, happiness, security, and safety. (Or if you’re a comic book arch villain — chaos.) Instrumental values are those values you hold dear in pursuit of your terminal values. Examples include being loving, obedient, independent, logical, or responsible.

Your values are the things that you believe are important in the way you live and work.

They (should) determine your priorities, and, deep down, they're probably the measures you use to tell if your life is turning out the way you want it to.

What we value guides our decisions and actions. Values are distinct to each individual so each person makes different decisions based on their defined values. One person may highly value gathering with family and friends; choosing a home with a large entertaining space. Another person may value simplicity and choose a small, easy to clean home. A third person might value their perceived status and choose an ostentatious home. There is more than one path to the top of the mountain.

Principles

“The intelligent have plans; the wise have principles.”

~ Raheel Farooq ~

Facts and situations are typically murky. As a result, humans and organizations establish principles as a guide for how to make decisions and act; and they are driven by the values of their creator.

Principles counter the knowledge problem of policymaking. They are short, pithy ground rules for engaging with a wide variety of situations. They do not suggest specific actions, but they do suggest specific kinds of actions.

Examples of principles include “always be kind”, “first, do no harm”, “rigorous honesty”, and “if it feels good, do it”.

Our beliefs/opinions drive our values, from which we set our principles.

Its all imperfect

All of these tools that our brains use to fill in the blanks are imperfect, but useful. Where they fail us most is when we forget that they are guidelines, subject to error and misuse. Some examples:

Overfitting

Overfitting is a term normally associated with machine learning, but it also applies to the errors we make when pattern matching. These can include mistakenly incorporating irrelevant data into a pattern and failing to apply a useful pattern to broader circumstances.

False memories/Memory distortion/Mandala effect

As details fade from our memories, that is if we ever did remember the details, our brain works to fill in these blanks with manufactured memories. They are just as real to us as our actual memories.

But the real surprise for us was the second most common type of error. The average person, under ideal viewing conditions, made one and one-quarter errors of the imagination. In other words, people just made things up. Without knowing they were doing it.

This is more common than we realize. Captain Kirk never said “Beam me up, Scotty”. Ed McMahon was not the spokesperson for Publishers Clearing House Sweepstakes. Dorothy didn’t say “Toto, I don't think we're in Kansas anymore." There is no major peanut butter brand called “Jiffy”. The Monopoly character doesn’t have a monocle. There is no breakfast cereal named “Fruit Loops”. The quote from Field of Dreams isn’t “Build it, and they will come”, nor did Darth Vader ever say “Luke, I am your father”, Forest Gump didn’t say “Life is like a box of chocolates”, and Roy Schneider didn’t say “We’re going to need a bigger boat” in Jaws.

So, yes, it’s always a good idea to double check your facts.

Illusions

I covered this above as an example of the brain manufacturing information, but it’s also an example of the brain filling in false visual information.

"If you didn't have the brain filling in all of this missing information, every time you looked at an object from a slightly different view, it would be a different object and that would be very confusing and difficult to cope with," says Patrick Bennett, associate professor of psychology at U of T and the study's other senior author.

"This filling in gives some consistency and continuity to the world."

While examining illusions can be a fun pastime, illusions have real consequences when we rely on eyewitness testimony. They can cause us to misjudge distances or see an incorrect trajectory.

Visual illusions occur due to properties of the visual areas of the brain as they receive and process information. In other words, your perception of an illusion has more to do with how your brain works -- and less to do with the optics of your eye.

An illusion is "a mismatch between the immediate visual impression and the actual properties of the object,"

Superstitions

“Fear is the main source of superstition, and one of the main sources of cruelty. To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom.”

~ Bertrand Russell ~

Superstitions, a mistake in a cause and effect that is solidified with confirmation bias, is an error in pattern matching. The person believes that an action or ritual will positively or negatively affect an outcome. While few still throw salt over their shoulder anymore, there are still many who have “lucky shirts” or engage in a ritualistic routine before a big game. Superstitions can be quite debilitating for some, but can also help the individual calm their nerves and focus on a task.

Superstitious people often experience a neurotic paradox, which is when they engage in a certain behavior because they don’t want a certain outcome, and – after doing the behavior – it doesn’t happen. For instance, if a person walks around a ladder instead of underneath it and nothing bad happens to them, they feel as though they avoided “bad luck” or misfortune.

“You think it works, so the behavior persists,” Storch said. “That’s one of the reasons you see these behaviors continue for a lot of people. They see a truth to it because the feared outcomes didn’t take place.”

Stereotyping

“I imagine hell like this: Italian punctuality, German humour and English wine.”

~ Peter Ustinov ~

As mentioned earlier, humans have evolved to be pattern matching machines. We fill in what we don’t know with templates created from similar experiences. This serves us well, most of the time, as it’s an efficient (if not always accurate) method of working around uncertainties. It’s hard baked into our DNA from thousands of years of avoiding dangerous out-groups and predicting behavior by their tribal membership.

Psychologists once believed that only bigoted people used stereotypes. Now the study of unconscious bias is revealing the unsettling truth: We all use stereotypes, all the time, without knowing it. We have met the enemy of equality, and the enemy is us. …

The cognitive approach refused to let the rest of us off the hook. It made the simple but profound point that we all use categories—of people, places, things—to make sense of the world around us. "Our ability to categorize and evaluate is an important part of human intelligence," says Banaji. "Without it, we couldn't survive."

The problem with stereotypes today is that society is far more complex. Groups are far less homogeneous than in centuries past. Individuals belong to many tribes, often with conflicting value systems. Attempts to define individuals by their group membership, trait, or appearance have high levels of error. This is compounded further by social media where groups form with shared distortions about shared out-groups. The result is stereotyping that undermines knowledge and understanding, instead of assisting it.

Misjudging similarity

“The fact that we're all different is the one thing we all have in common.”

~ Justin Young ~

This is another pattern matching error. We make decisions based on circumstances being similar to a time before, but we’re wrong. We sometimes believe that someone is a member of a shared tribe, with its shared values, but they aren’t.

Changing times

“Change is an unsuspecting and finicky foe. You don't realize the strength of its grip until it's too late.”

~ Dave Cenker ~

This is phenomena that all parents will recognize. A parent finds a way to motivate or compel their kids only to find that their ‘trick’ no longer works. Companies find a successful niche only for it to fade away or promote a product that loses its appeal to the masses. Times change and the patterns we detect can change over time. The shortcuts we develop sometimes stop working. It’s a mistake to assume that what once worked will always work and we can be painfully slow to recognize that the times have changed on us.

Putting this all together

As amazing as our 3 pound brains are, they have a limited capability to take in information, retain that information, and still make 35,000 decisions a day. To do so, the brain has numerous strategies to accomplish this, including:

When needed information is missing, the brain pulls clues from the words and behaviors of those around us, favoring our in-groups and those in authority.

The brain will search for patterns that can be applied to the current decision.

The brain will fill in the missing information by creating a memory that fits with the existing knowledge.

The conscious brain will make decisions based on the beliefs, rules, and values the individual has developed over time.

Or, the brain may choose the quickest option — to repeat the decision that was used the last time the situation came up.

All of these adaptations are imperfect and can result in bad outcomes. In a healthy system, the brain (hopefully) learns from those mistakes and makes a different decision the next time.

Where these adaptations fail is when the person assumes perfection in their decision making process, whether it be the belief that their memories are perfect or that their conclusions are infallible. This is further complicated by our subconscious drive to preserve our reputation by vigorously defending our decisions and related opinions.

By recognizing how our brain makes decisions, and the weaknesses in that process, we can spot our errors quicker and reduce their quantity.

Exercises

To be done in a non-distracting environment:

Identify a decision you recently made based on spotting a pattern.

Identify a decision you’ve recently made despite not having enough information. Which of the above methods did you use to come to that decision?

Identify a decision you’ve made that was made about an individual that was made without conscious thought.

Finale

This is the fifth foundational essay for this newsletter. Last week we covered how the people around us influence our decisions. The next foundational essay will cover human error and how we adjust to those errors.

Thank you for visiting today. Your readership is greatly appreciated and valued. If you found this newsletter interesting like and comment below. Please recommend this newsletter to friends and family who might find this content interesting. Have a great week!

Your friend,

DJ

As I read the very first section of this piece about Olive, it took me back to the midh seventies when my friend Mark (who is likely reading this) and I learned all about Aerosmith's amazing new song from our friend John that neither of us had heard of this new song that was apparently called...

Doctor Spain